The Arc of Cruelty - The Taboo Twins: Envy and Schadenfreude

Exploring the Spectrum of Sadism

What if I told you that almost everyone harbours a little bit of sadism within them?

Imagine scrolling through your social media feed during a frustrating job hunt or amidst a string of disappointing dates. Suddenly, there it is: your friend's exuberant post about landing their dream job or finding 'the one.' You reach to tap the like button, but your finger hovers for a moment as a familiar pang of jealousy tightens your chest. Fast forward a week, and you catch yourself smirking at their status update about a rough first day or a lover's quarrel. Admit it, you've been there.

We've all had those moments, especially when our own careers or love lives hit a dry patch. These fleeting bursts of envy and schadenfreude are the mischievous twins of human emotion that often lurk in the shadows of our psyche. As a psychotherapist, I’ve had the rare privilege of hearing people muster the courage to voice these feelings, often sheepishly at first. But their honesty, in the face of what society tells us is taboo, never ceases to move me.

Why do we hide it?

Society has trained us to see any hint of sadistic pleasure, no matter how mild, as fundamentally wrong, even evil. This leaves many of us wrestling with the fear that such thoughts make us monstrous, unrelatable, or inherently flawed. But in my years of practice and my own personal experiences, I’ve come to see that these reactions, while seldom discussed openly, are far more common than we'd like to admit. Just because it’s taboo doesn’t mean it’s rare; in fact, it’s surprisingly common, just often hidden from view, like that embarrassing photo from high school you hope never resurfaces. Ahem, moving right along…

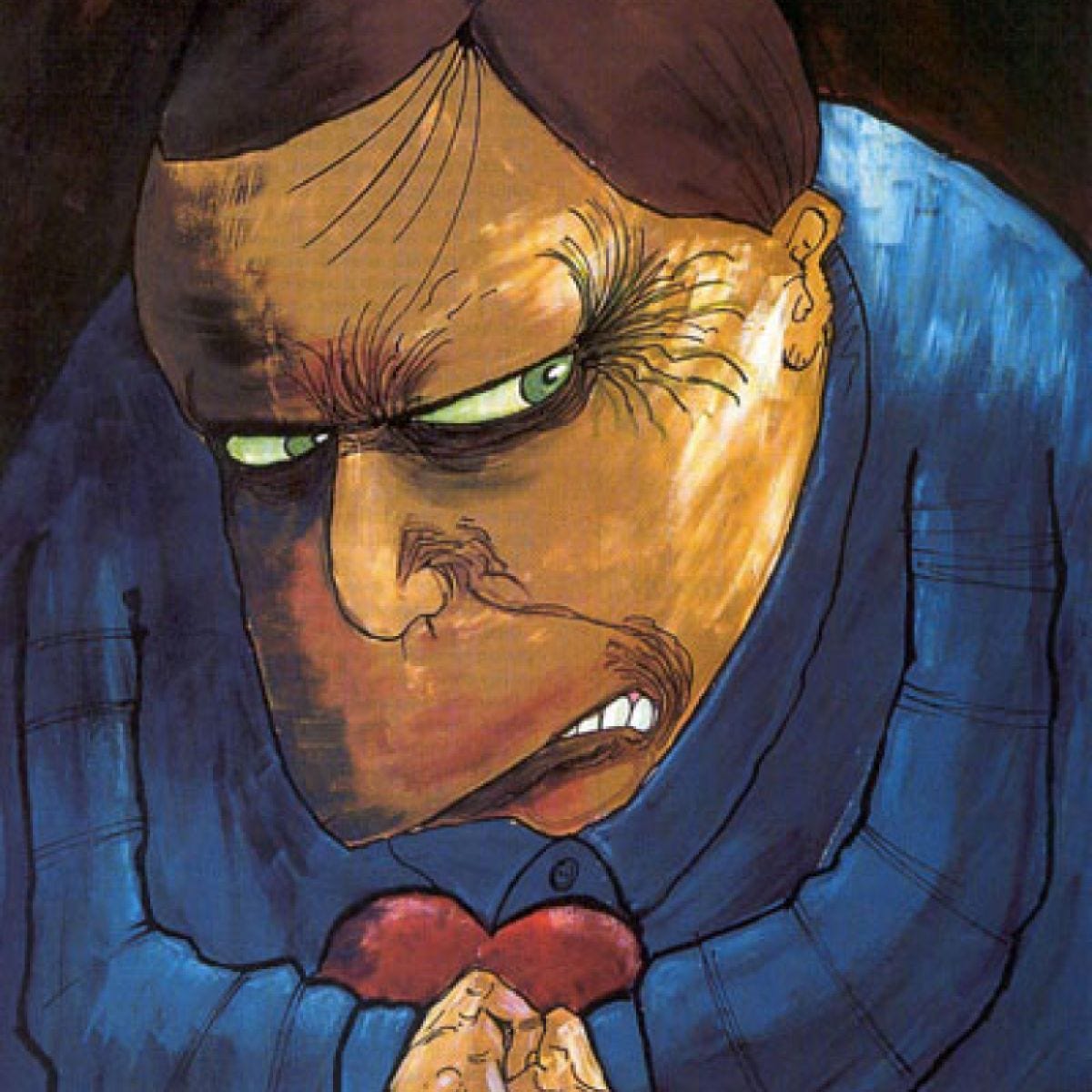

Sadism, simply put, is deriving pleasure from others' discomfort. But it's not just confined to the extremes of psychopathy or the villains in movies with their evil laughs. Sadistic tendencies are disturbingly common, embedded in everyday interactions. The fact that we often overlook or downplay this prevalence is exactly what makes it so insidious. While you may never cross paths with a true psychopath, sadistic behaviours impact all of us - sometimes subtly, sometimes overtly, but always harmfully. After all, experiencing sadism always hurts - that's the point.

Recognising sadism’s varied forms and intensities is not just an academic exercise but a crucial step in understanding and navigating the social world we live in. By acknowledging its presence and inherent capacity to harm, we can start to address its impacts and work toward healthier interactions.

But is it just us?

Before diving into human sadism, let's consider our primate relatives. Many traits associated with the Dark Triad (psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism) have evolutionary roots and are not exclusive to humans.

Chimpanzees, for instance, exhibit behaviours that mirror aspects of the Dark Triad. They engage in deception, form strategic coalitions, and display aggression to enhance their status within the group. Male chimps might even kill infants to bring females back into oestrus, increasing their own reproductive success. These behaviours, while seemingly cruel, are driven by survival instincts rather than pleasure derived from others' suffering.

What sets humans apart is our cognitive complexity, particularly our advanced Theory of Mind. This ability to understand and predict others' mental states not only aids in social cooperation but also allows for the possibility of intentionally causing mental distress for personal pleasure. This capacity for sadism - deriving pleasure from others' pain - appears to be uniquely human.

In this series, we’ll explore together the breadth of this continuum, examining how sadistic tendencies manifest in different forms and intensities. We’ll delve into how these actions affect our relationships, workplaces, and broader society. So, buckle up, and let’s dive into the disturbing yet all-too-familiar world of sadism, starting with a closer look at our 'good friends,' envy and schadenfreude.

Social Comparison: The Foundation of Envy and Schadenfreude

Social comparison, the foundation of many of these reactions, acts as our brain's built-in GPS, constantly recalculating our position in the social landscape. It's this mechanism that gives rise to envy when we perceive others as having advantages we lack, and schadenfreude when we take pleasure in others' misfortunes.

These emotions, while often viewed negatively, have played significant roles in our evolutionary history. They can motivate us to improve our own status, foster group cohesion, and navigate complex social hierarchies. However, when taken to extremes, they can also lead to destructive behaviours and a lack of empathy.

Envy: The Green-Eyed Monster

Envy has deep roots in human culture and psychology, perhaps best exemplified by the concept of the Evil Eye. This ancient belief in a curse cast by a malevolent glare, fuelled by envy, spans cultures worldwide. From ancient amulets to modern-day gestures, humans have long been preoccupied with warding off the perceived dangers of others' envious gazes. The prevalence of Evil Eye beliefs underscores how seriously humans have taken the threat of envy throughout history. It's not just about feeling bad – it's about the fear that someone's envy could actively harm you.

At its core, envy arises from social comparison. As social beings, we constantly evaluate our status relative to others. This comparison helps us understand where we stand in the social hierarchy and motivates us to improve. Evolutionary psychology suggests envy evolved as a mechanism to compete for resources and mates, playing a crucial role in our ancestors' survival and reproductive success.

Envy comes in two flavours:

Benign Envy: This can inspire us to work harder and achieve more. Seeing a colleague's success might motivate us to develop our skills and strive for similar achievements.

Malign Envy: This darker form can lead to destructive behaviours. As the saying goes, "If I can't have that, I'll make it so no one can." Malign envy can cause individuals to sabotage others, spread rumours, or engage in unethical behaviour to undermine their rivals.

When envy becomes maladaptive, it leads to negative feelings and destructive behaviours. In evolutionary terms, maladaptive envy can be seen as a strategy to eliminate competition, although it often backfires by damaging social relationships and trust.

Schadenfreude: When Misery Loves Company

Schadenfreude, it's a mouthful, but we've all felt it. This German word describes the pleasure derived from others' misfortunes, and it's a common form of mild sadism. Think about those moments you chuckle at a celebrity's public blunder or a reality TV star's meltdown. While schadenfreude can reinforce social bonds by creating a shared sense of superiority, it's socially taboo in many cultures and even lacks a common word in English (well, there is epicaricacy but I’d wager few of us have ever heard it).

Crucially, schadenfreude is about pleasure in witnessing discomfort for others, as opposed to causing pain actively. This is where we start to see the shift towards actual sadism. Schadenfreude is passive; sadism is active.

Deeply connected to social comparison and competition, schadenfreude can provide a sense of relief when a rival experiences a setback, temporarily boosting our own perceived status. Evolutionarily, this behaviour could have strengthened group cohesion by collectively relishing the downfall of outsiders or rivals.

However, the darker side of schadenfreude reflects a lack of empathy and a propensity for cruelty. Individuals who frequently experience schadenfreude might have narcissistic traits and empathy deficits, potentially escalating into more severe forms of sadism.

The Deservingness Factor

An important aspect of schadenfreude is the concept of perceived deservingness. Our enjoyment of others' misfortunes often hinges on whether we believe the person "deserves" their fate.

Just World Fallacy: This psychological concept reflects the bias that the world is inherently fair, and people generally get what they deserve. This can make it easier to feel schadenfreude, especially when we perceive that someone’s misfortune is a form of justice. However, this mindset can also underpin harmful attitudes like victim blaming, where we rationalise that those who suffer must have done something to warrant their plight.

Karmic Justice: Closely related to the Just World Fallacy, this concept involves the idea that a person’s actions - especially negative ones - will inevitably lead to their downfall. When we see someone who has wronged others experience misfortune, it can trigger a sense of satisfaction, as if balance has been restored.

Moral Licensing: Moral licensing allows us to justify our enjoyment of others' misfortunes by focusing on their perceived flaws or wrongdoings. By convincing ourselves that someone’s negative traits or actions warrant their suffering, we can indulge in schadenfreude without guilt. It’s a mental loophole that helps us reconcile our pleasure with our moral standards.

The Envy - Schadenfreude Connection

Envy and schadenfreude are like two sides of the same emotional coin, both minted in the currency of social comparison. Envy is the pain we feel when the coin lands heads-up, showing us someone else's success. Schadenfreude is the pleasure we experience when it flips to tails, revealing another's misfortune.

Psychological research reveals these emotions are intimately linked. Envy acts as an emotional powder keg, with a rival's misfortune serving as the spark. Studies show that the more intensely we envy someone, the more likely we are to experience heightened schadenfreude when they stumble, especially in competitive social situations. This burst of pleasure is particularly potent when it involves an envied rival's failure.

From an evolutionary perspective, this connection makes sense. If we perceive someone as a rival due to envy, their setbacks become opportunities to improve our relative social standing. It's as if our brain is constantly keeping score, and schadenfreude is the reward we feel when the points shift in our favour.

However, this envy-schadenfreude cycle can be psychologically toxic, potentially pushing us further along the spectrum towards more active forms of sadism. As we navigate these complex emotions, the goal isn't to eliminate them—they're part of our evolutionary heritage—but to understand them, control them, and hopefully, channel them into more constructive outlets. After all, deriving pleasure from others' misfortunes is a slippery slope that can lead to darker territories of human behaviour.

Diving Deeper: The Hidden Role of Shame

If we peel back the layers of envy and schadenfreude, we uncover a more profound, often unacknowledged emotion lurking beneath the surface: shame. If envy and schadenfreude are the visible actors on the stage of our social interactions, shame is the unseen puppeteer, pulling the strings behind the curtain.

Shame is considered by many sociologists to be the master social emotion playing a significant role in regulating our behaviour and self-perception. Yet shame is culturally taboo in Western societies. Sociologist Thomas J. Scheff notes "We are so ashamed of shame that we pretend it doesn't exist." This meta-shame, being ashamed of feeling shame, creates a complex emotional landscape where we often struggle to acknowledge or address our shameful feelings directly.

The renowned emotion researcher, psychologist Paul Ekman, didn't include shame in his 2003 book ‘Emotions Revealed’ on the core emotions because it doesn't manifest on the face but rather in the body: slumped shoulders, averted gaze, or withdrawal, an issue he talks about in this interview. This physical manifestation highlights shame's deep-seated nature and its profound impact on our social interactions.

Shame intimately connects to both envy and schadenfreude, often serving as the hidden driver for these emotions.

Shame and Envy: When we feel inferior or inadequate compared to others, we experience shame. This shame can manifest as envy, a more socially acceptable way of expressing our feelings of inadequacy. Instead of acknowledging "I feel ashamed of my lack of success," we might think, "I envy their success." Envy thus becomes a defence mechanism against the painful experience of shame.

Shame and Schadenfreude: The pleasure we derive from others' misfortunes often stems from a temporary alleviation of our own shame. When someone we envy fails or suffers a setback, it momentarily boosts our self-esteem and reduces our feelings of shame. The thought "At least I'm not as bad off as them" provides a brief respite from our own feelings of inadequacy.

By recognising the hidden role of shame in envy and schadenfreude, we can better understand these emotions' deeper roots and begin to address them more constructively. Rather than allowing shame to operate from the shadows, bringing it into the light can help us develop greater emotional awareness and healthier ways of managing our social interactions.

In part two of this article, available here, I’ll be exploring envy and schadenfreude in the modern world and offering some strategies for managing these emotions in healthier ways.

Thank you Paul for such a clear and illuminating description of envy and Schadenfreude. Very important to be able to think about these feelings more openly to understand ourselves more compassionately.