Psychopathy and Psychotherapy in Public

Reflections on the Goldwater Rule tightrope walk

Let’s be honest. Diagnosing public figures has become a popular national pastime, with people often playing amateur psychologist especially during election season. Picture a family gathering where everyone suddenly morphs into Freud, casually throwing around diagnostic terms like "narcissist", “paranoid”, “delusional” and “psychopath” as easily as they pass the mashed potatoes.

The irony here is that because of my training as a psychotherapist, I’m assumed to be able to use diagnostic terms accurately and that’s exactly why I shouldn’t say them - at least not publicly. And that’s a little troubling. At times, I’ve felt a bit like the proverbial “ambulance at the bottom of the cliff”, helping people recover from the trauma of their prior contact with psychopathic individuals - whether it’s a con-artist, a work-place bully, an abusive partner or a cult leader - who they didn’t recognise for what they were - until some real harm had been done.

Have you ever watched a tightrope walker at the circus? There they are, balancing precariously on a thin wire, audiences holding their breath with every step. Now, imagine that tightrope is the line between ethical psychotherapy writing and public curiosity, and the walker? Well, that's me, a psychotherapist, especially when it comes to discussing psychopathy (and other psychological peccadilloes) in the public sphere.

Psychopathy: Not Just a Hollywood Script

When you hear "psychopath," your mind might jump straight to a thriller movie villain – cold, calculating, and probably with a secret lair. But let's cut through the dramatics. Psychopathy, in the real world, isn't about dramatic monologues or evil geniuses. It's a complex personality disorder characterised by a range of traits like lack of empathy, superficial charm, and often a disarming amount of charisma. Yes, they're often the life of the party, not the one lurking in the shadows!

Debunking Some Movie Myths

Myth 1: "All psychopaths are dangerous criminals." False: While some Hollywood blockbusters might have you believe that every psychopath is a Bond villain in a high-speed chase, in reality, not all individuals with psychopathic traits end up breaking the law. Some might be breaking hearts (or at least trying to), but not always laws.

Myth 2: "Psychopaths have no emotions." False: They do experience emotions, but perhaps not the full spectrum or depth that others do. Think of it as watching TV with the colour settings off. There's still a picture, but it's not quite as vivid.

The Serious Side of Psychopathy

Despite my light-hearted start, psychopathy is a serious subject, especially in social and professional contexts. People with these traits can significantly impact those around them, often leaving a trail of complicated interpersonal relationships. In the workplace, they might be the charming colleague who's mysteriously never at fault, or in a family setting, they could be the Aunt everyone tip-toes around. Understanding the nuances of psychopathy is crucial not just for psychotherapists, but for anyone who finds themselves trying to navigate these complex human interactions.

Now psychopathy is a subject I plan to delve into from a psychotherapists perspective in future posts. So what’s the problem? Well, understanding psychopathy in its true complexity sets the stage for appreciating the ethical nuances in discussing mental health publicly. This brings us to an essential cornerstone of professional ethics in mental health discourse: the Goldwater Rule.

The Goldwater Rule - A Brief History

The Birth of the Rule: More Than Just a Gentleman's Agreement

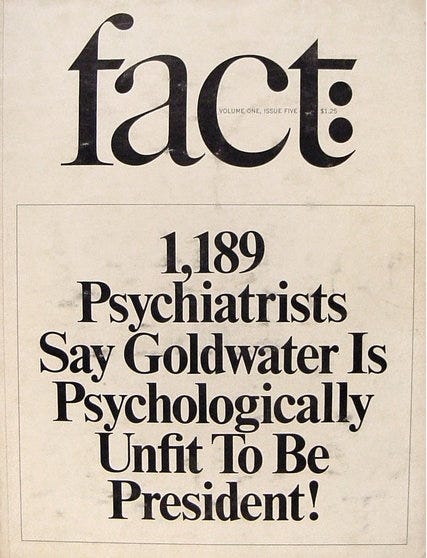

It's 1964, and Senator Barry Goldwater is running for president. A magazine, "Fact," runs a survey asking psychiatrists whether they believe Goldwater is psychologically fit to be president. Many psychiatrists took the opportunity to play armchair quarterback, diagnosing Goldwater with everything from paranoia to megalomania.

Goldwater went on to lose the election to Lyndon Johnson in a landslide, with one of the biggest losing margins in history. Goldwater sued the magazine for libel and won which prompted the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to establish the Goldwater Rule, essentially saying, "Dear Psychiatrists, please don't diagnose people you haven't personally examined without their consent. Sincerely, Common Sense (and now your Ethics Code)." Another APA, the American Psychological Association helpfully issued an essentially identical statement for psychologists so that it wasn’t too confusing with there being two of them.

It's like telling chefs they can't critique a dish they haven't tasted or telling a mechanic they can't diagnose a car's problem without looking under the hood. Now this all seems ethical and appropriate, right? Largely, I’d agree. But it does get a bit tricky especially around things like psychopathy because few psychopathic individuals ever willingly sit for a formal diagnostic interview or consent to anyone sharing the outcome for the obvious reasons that it might attract unwanted stigma or attention.

Most diagnoses of psychopathy happen during court trials when a defendant pretends to have a different mental health condition in an attempt to avoid conviction or reduce any sentence. Historically, a pretence at some form of temporary psychosis was common, but more recently and outrageously, misuse of an Autism diagnosis was attempted. Just to be clear, Autism already attracts far too much social stigma and has absolutely nothing to do with murdering people, something the court thankfully recognised. Anyway, when this ruse fails, the psychopathy behind it is diagnosed. Well, anti-social personality disorder technically [These various different terms - psychopath, sociopath, anti-social, malignant narcissism - are something I’ll be exploring in a future post]. This pattern has not helped the public misconception that psychopaths are all criminals.

So have psychopathy and the Goldwater Rule collided? Yeah, just a little.

Donald Trump and A Whole Lot of Controversy

Fast forward to the 2016 presidential election, and the Goldwater Rule is back in the spotlight. A group of mental health professionals wrote a book "The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump," arguing that Trump's behaviour suggested various psychological disorders. This was a direct challenge to the Goldwater Rule and many mental health professionals decried the books content.

The American Psychiatric Association responded by reiterating the Goldwater Rule, cautioning against the ethical risks of mental health professionals making public diagnoses without proper evaluation.

Walking The Ethical Tightrope: Public Safety vs. Professional Ethics

So here's the pickle – when do mental health professionals' responsibilities to the public override the Goldwater Rule? On one side, there's the ethical duty to keep mum on public figures' mental health. On the other, there's the urge to weigh in on what you think could be a walking textbook case of [insert disorder here]. Some argue there's a "duty to warn" when a public figure might pose a risk to public safety.

With the benefit of hindsight, I think both APAs were right in this instance. It’s not like Donald Trump ended up being the ‘clear and present danger’ that these rogue clinicians worried he might be. He’s only been impeached twice, criminally indicted quarce (yes, it’s a word) and become an election-denying insurrection-causing threat to the future of American democracy. [That was sarcasm BTW, the lowest form of wit but the highest form of intelligence, per the research.]

While psychotherapists need to tread carefully around ethical concerns, we also can play a crucial role in educating the public about mental health and psychological safety. So, how can I contribute without overstepping ethical boundaries? Perhaps by offering general insights into behaviour and mental health, or discussing historical figures where the context and consequences are clearer. It's a bit like being a guide in a psychological hall of mirrors – helping the public navigate without getting lost in reflections of diagnoses.

Now, as it turns out the American Psychoanalytic Association (APsA) [yes, I know that’s THREE professional associations now] has long taken a softer stance. Amidst the furore about the book, they noted that a psychoanalyst musing somewhat diagnostically about a political figure was not considered unethical, as long as it was offered thoughtfully and not recklessly.

Now, as a psychotherapist who leans somewhat more towards psychoanalysis than psychology [I’ll be writing about that difference too!] in a different hemisphere, can’t I just ignore the Goldwater Rule and fire away? Maybe. But that doesn’t sit right with my personal code of ethics.

Ethical Challenges Beyond the Goldwater Rule

In the grand arena of psychotherapy, the Goldwater Rule isn't the only high-wire act. Lately, a concerning wave has been crashing through our professional shores: some health and education experts are pushing narratives that clash with science and ethics, particularly around anti-vaccine claims and anti-trans rhetoric.

These viewpoints, echoing loudly in the digital megaphone of social media, present real ethical dilemmas. When professionals back anti-vaccine ideas, they're essentially playing with fire, jeopardising public health based on unscientific claims. And when they support anti-trans narratives, they're not just on the wrong side of history; they're actively harming some of the most vulnerable among us. This isn’t just a misstep; it’s a leap away from our duty to do no harm, respect diversity, and stay rooted in credible scientific evidence.

As a psychotherapist, watching colleagues blur these ethical lines is both disappointing and alarming. It underscores why we need to stick not just to the Goldwater Rule but to our broader ethical compass in all we say and do publicly. Whether it’s discussing the mind's labyrinths or societal issues, our words should be built on a foundation of evidence, empathy, and an unwavering commitment to improving public understanding and welfare.

In my upcoming writings, I plan to tackle these ethical mazes head-on. Navigating mental health topics requires a delicate touch, especially with the public's ear so finely tuned in. In this balancing act, I aim to enlighten, engage, and maybe, just maybe, entertain, all while holding tight to the ethical reins that guide our profession.

And who knows? With a dash of humour and a heart full of care, we might all just make it across this tightrope without falling into the abyss below.

I’d like to hear what others think on all this so comments on this post are open to all.

Nice piece of writing Paul. I'd not heard about the Goldwater Rule, but appreciated your investigation into the potential challenges and contradictions there. As another therapist, I face this when clients discuss another person in their life, especially one that is causing them a great deal of distress. In the interests of 'better the devil you know', and 'keep your enemies closer', it can be very helpful for the client to gain a better understanding of the likely psychological dynamics of the person they are dealing with. However, of course, we are gaining information on that third party through the filter of our client's experience, and not, as the Goldwater Rule points out, through direct contact or clinical examination of that person. Thanks for the thought-provoking piece. I look forward to what more is to come!